Introduction to Gendered Applications

As every aspect of our lives becomes increasingly digital, so have our medical and reproductive health information. With the development of new applications that allow women to track their sex lives, periods, and pregnancy comes bias and variance across platforms. The fact that a vast majority of app developers are men is extremely concerning when it comes to their ability to understand women’s varying needs and stages of their reproductive and sexual lives. What has been extremely prevalent is the one-sidedness of applications. Pregnancy is romanticized and painted as the only option on some apps. There is often not an option for avoiding pregnancy. This is proof of the existence of femtech and of the way that online media is controlled in a way that restricts women.

Apps and Pregnancy

In the article “Barbies, Goddesses, and Entrepreneurs” stereotypical “subject positions” in the topic of women’s health online are discussed. Although they are given the choice of their health outcomes, the fact that there is a limited range of outcomes heavily influences women. One instance of this, for example, is the fact that pregnancy apps promote “personification of the fetus”. This bias towards the choice to have a child alters the user’s mindset and makes it much more likely for the women to become an “advocate of the fetus”. Reproductive apps often do not understand the concept of choice at all; it is a common occurrence that they will interpret missing periods as pregnancy, when in fact it could be that the women had an abortion or a miscarriage. As Olga Massov discusses on Mashable, many women often have to reset or redownload their apps after one of these events occurs because it completely destroys all the data they have built up. These harmful algorithms perpetuate the idea that having babies is at the center of women’s health.

“Barbies, Goddesses, and Entrepreneurs” also explored the bias that exists even for women who are indeed going through a pregnancy. Icons for these apps often depict the female body as slim and beautiful even during a pregnancy. Apps’ icons and descriptions place fertility at the center of sexuality and womanhood, and encourage discretion about sexual activity. They also often include images of nature and beauty, emphasizing that having children is the natural way of life and reinforcing the idea that infertile women are unnatural.

Apps and Sexuality

Apps that do place sex in the center of reproduction, however, are often extremely sexist. There is one app in particular that Miranda Hall discusses on Vice that allows a woman’s partner to be synced in to her reproductive and medical information. When women are ovulating, the app pushes them a notification to put on “sexy underwear”, and pushes the man to “buy flowers on the way home”. Miranda posits that the way the app automatically lets the partner know that the woman wants to have sex is extremely disempowering. Apps like these take away a woman’s right to take charge of both her sexuality and her fertility, and placing it into a man’s hands once again. A large percentage of app developers are men, begging the question of if they even know enough information to properly cater to a woman’s reproductive needs.

Survey & Interview

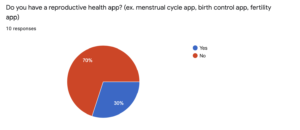

In order to get a feel for how some of the women around me (specifically college-aged women) are affected by feminine digital media, I conducted a survey about the reproductive applications they have on their phones.

It came as a shock to me that so few of them had reproductive health apps, seeing as we are women in college, but nevertheless, the ones that did have them continued on with the proceeding questions.

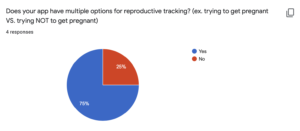

I was happy to see that the majority of women who did have health apps were able to input varying forms of reproductive information (they weren’t forced to behave as if they were trying to get pregnant, etc.)

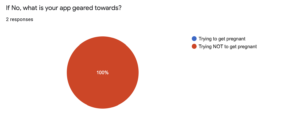

Again, the one person that did have a one-sided app, had one that was more geared towards pregnancy prevention. In order to interpret these results more closely, I decided to interview one of the girls that completed the survey.

Transcript:

“So I know that you answered that you have a reproductive health app, what kind of information do you put into it?”

“I put the days in which I’m on my period, how heavy the flow is, the symptoms I have like cramps, backaches, fatigue, and I log my sleep and the activity that I do.”

“So do you put when you take your birth control in there at all?”

“No, they don’t have that option or at least I can’t find it because it doesn’t say. It does say though if you’d like had sex and stuff like that or like your sexual activity but they haven’t said like if you’re on birth control”

“So do you feel restricted in that way, that you can’t put your birth control in?”

“Yeah because I used to not be on birth control and I would have a period of like 5 to 7 days with worse symptoms, and so now when I log it it’s only like 4 days on my period, and less symptoms, so the app thinks I’m having irregular cycles even though they are regular, and I don’t know if it’s helping me as much”

Conclusion

The girl that I interview struggled with her app understanding that she was using a contraceptive, just liked many other women in the sources I used discussed. This is clearly a huge problem for women’s health, seeing as, especially in the time of Covid-19, medical information is moving into the digital world. The gendering of applications is very dangerous because it places women in a box. Yes, they can now take charge of their sexuality and feminitiy in the real world, but how are they supposed to do this digitally without the proper tools? The fact that pregnancy is the center of essentially all women’s health apps is upsetting for infertile women or women that just don’t want to have children at all. This emphasis on childbearing is frustrating in that women don’t really have any other choice but to go along with it because of the lack of well-developed apps that are avaliable. Developers of reproductive health media need to work with women so that they can get what they need out of the applications avaliable to them, because it is obviously not satisfactory for a majority of women.

Sources

Doshi, M. J. (2018). Barbies, Goddesses, and Entrepreneurs: Discourses of Gendered Digital Embodiment in Women’s Health Apps. Women’s Studies in Communication, 41(2), 183-203. doi:10.1080/07491409.2018.1463930

Massov, Olga (2018). Pregnancy apps don’t know how to handle miscarriages, Mashable https://mashable.com/article/miscarriage-stillbirth-pregnancy-apps/

Hall, Miranda (2017). The Strange Sexism of Period Apps, Vice https://www.vice.com/en/article/qvp5yd/the-strange-sexism-of-period-apps